A Critical Review of “1787: The Grand Convention” by Clinton Rossiter

Introduction

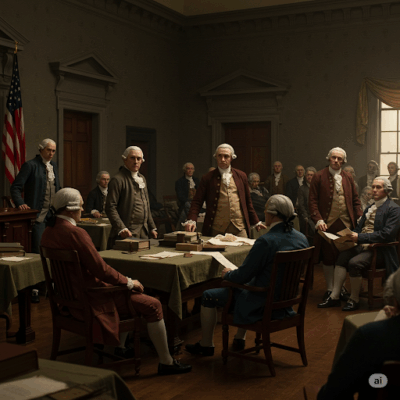

Clinton Rossiter’s “1787: The Grand Convention” provides a comprehensive examination of one of America’s most pivotal historical moments—the Constitutional Convention of 1787. The book carefully divides this watershed event into four distinct sections: The Setting, The Men, The Event, and The Consequences. This structure allows readers to understand not just what happened in Philadelphia that summer, but why it happened and who made it possible.

The Setting: A Nation in Crisis

Rossiter begins by painting a vivid picture of a young nation experiencing severe growing pains. The United States under the Articles of Confederation was functioning, but only barely. The central government lacked sufficient power to address mounting economic problems, interstate disputes, and foreign policy challenges. Without significant reform, the fragile experiment in democracy risked collapse.

What makes Rossiter’s account particularly insightful is his emphasis that revolution alone was insufficient—winning independence was only the first step. The more complex challenge lay in creating a functional government that could unite thirteen diverse states with competing interests. The country resembled quarreling siblings rather than a unified nation, and it became increasingly clear that something had to change to preserve what the Revolution had achieved.

The Men: More Than Just Famous Names

The book excels in its detailed portrayal of the Convention’s delegates. While most Americans recognize figures like Washington, Madison, Hamilton, and Franklin, Rossiter introduces readers to the full assembly of contributors. These delegates weren’t abstract historical figures but complex individuals—all well-educated, politically experienced, and predominantly from privileged backgrounds.

Rossiter humanizes these founders, moving beyond the simplified, almost mythological portrayals often presented in basic education. We discover men with flaws, ambitions, and conflicting interests who somehow managed to work together despite their differences. This section fills crucial gaps in our understanding, giving life to names that might otherwise receive only passing mention in history textbooks.

The Event: A Difficult and Contentious Process

Perhaps the most enlightening portion of the book covers the Convention itself, which spanned from May 14 to September 17, 1787. Rossiter dispels any notion that the Constitution emerged from a harmonious process. Instead, he reveals:

- Poor attendance was common, with many delegates arriving late or departing early

- Rhode Island refused to participate entirely

- Delegates often held deeply incompatible views about the proper structure of government

- Compromise was difficult and sometimes reluctant

- Some delegates, like Hamilton, who had been instrumental in calling for the Convention, participated minimally (attending roughly 10% of the sessions)

- Others, like William Patterson, proposed plans and then rarely returned

The Convention featured heated debates, frustrating impasses, and periods where the entire project seemed in jeopardy. This portrayal stands in stark contrast to the smoothly functioning, inevitable process often suggested in simplified historical accounts.

The Human Side of History

Rossiter excels at revealing the humanity behind these historical figures. Many delegates, despite their contributions to American governance, suffered financial difficulties later in life. James Wilson, a significant contributor to the Constitution, died in debtor’s prison. These personal struggles underscore that the founders were not the demigods of popular imagination but actual people with weaknesses and limitations.

What emerges is a more authentic understanding of how democratic governance develops—not through the perfect actions of flawless individuals, but through the combined efforts of talented yet imperfect people working through disagreement toward a common goal.

The Value of Historical Truth

Rossiter’s work serves as an essential corrective to what might be called the “Mickey Mouse version” of American constitutional history. By incorporating carefully selected quotations and primary source material (particularly James Madison’s detailed notes), the book provides a more nuanced understanding of this formative period.

The author maintains reader engagement despite the complexity of the subject, though at times the text becomes dense with references to lesser-known delegates, which can slow the reading experience.

Conclusion

“1787: The Grand Convention” offers an invaluable perspective on the messy, difficult process of nation-building. The miraculous aspect of the Constitutional Convention isn’t that perfect people created a perfect document—it’s that despite significant differences, personal rivalries, and competing visions, these delegates managed to forge a framework of government that has endured for over two centuries.

For anyone seeking to understand how America’s system of government came to be, beyond simplified narratives, Rossiter’s detailed account provides both historical accuracy and profound insights into the nature of democratic compromise and constitutional development.